We are staying in the Cihangir neighborhood of Istanbul. It is a real neighborhood. You will see wine shops, mehaynes (restaurants where you eat meze), cafes, counters stacked with börek (sweets made of pure goodness like honey, pistachio, rice, phyllo, walnuts, rosewater), piles of antiques, vintage clothing, and even furniture stores, where design and woodworking is done on site, of wood-carved rocking chairs with mod lines. The novelist Orhan Pamuk started his Museum of Innocence here.

Let me put it this way. While in every guidebook, you will hear about Istanbul’s famed Grand Bazaar and the Spice Market, those places are very much like tourist-headache neighborhoods back home, that spot where visitors beg to go (Bourbon Street in New Orleans, Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, Disney World in Orlando, I’m talking to you).

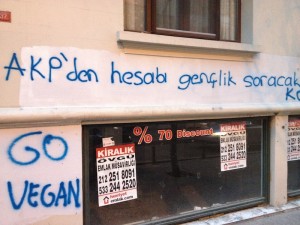

Cihangir, on the other hand, is your favorite neighborhood back home (Bywater, Mission District, and Thornton Park, respectively). The neighborhood you wish you had bought a house in when it was still seedy and affordable, like 5 years ago. You can see here the slow right-to-left gentrification.

But back to tear gas.

Cihangir is also very close to Taksim Square, a place protesters tend to organize. The square itself pours out onto the very busy, chain-store Istiklal (Independence) Street. This particular touring day, we were on our way to Istiklal to ride the old tram that lumbers down the street, and ooh-and-ahh over the Art Nouveau buildings now, sadly, filled with Mango, Diesel, and Lacoste.

I certainly saw no evidence of a late-1800s tram, but I did start to notice this on every corner:

Which seemed like a worrisome sign. I will say, though, the police seemed friendly, minus the shields and gas masks. They let me take photos after all.

Just past sunset, we heard voices chanting in the distance. Our Istanbul guide, Alp, translated: “Everywhere is Taksim. Everywhere is resistance.” He said it referred to the protests this past June and went on to explain some of the rules of protesting should we want to get involved in democracy. Kicking police shields is okay. You can push. But no throwing rocks at police.

As the volume of voices increased, like a drum beat getting nearer and nearer, Alp advised that we detour down a side street to watch safely from there. We gathered near a chestnut vendor, so when Alp said, “I smell gas…,” I responded with, “No, no. It’s okay. It’s just chestnuts.” But when the chestnut man started hacking and smoke filled the air, I realized Alp knew what the hell he was talking about. And not very lucky for us, a large group of people waving Communist flags took a left turn and marched down the side street we were on, drawing the police with them.

Alp looked at me, a little alarmed, and issued my order, “Run! I will meet you at the end of the street … But where’s Craig?” Alp backtracked and found him filming near Istiklal. We had yet to learn that Craig possesses some modern-warfare dermis that gives him an immunity to tear gas. Alp tugged him by the sleeve of his coat. We ran, but most of the tear gas had been set off ahead of us. We were essentially running into it, but we could no longer backtrack. Merchant gates were slamming shut; cafes chairs in the streets were being rolled inside.

In 10 minutes, we had lost the communist flag-police posse and found Susam Cafe, a wine and food bar hidden in the back streets of Cianghir, not far from our hotel. We ordered a bottle of wine from Azad, the Kurd waiter who is learning to speak English to win an English girlfriend back. We shared Craig’s footage with him.

[Footage is coming]After about an hour, the yelling and chanting increased again in volume. From the cafe window, I saw mobs of people running quickly from something, then shortly after the police with tear gas and water hoses. Protesters were hurling objects (uh-oh, rocks?). Tear gas filled the cafe. Craig, like a war reporter, shot out into the streets to get footage.

All of us in the cafe wrapped our scarves around our noses and mouths. My tongue tingled. Then the eyes. Azad gave me a bottle filled with white liquid and motioned for me to put it in my eyes. It was medicine for stomach acid but the remedy for stinging eyes. Never use water, said Alp. We passed the bottle from table to table. Eventually the protestors and police moved a few blocks down from the cafe. And everyone went back to eating and drinking, only not on the outside patio.

Craig returned about 45 minutes later with footage that I will post on You Tube when I get it from him.

Meanwhile, there really is such thing as a tear gas hangover. I woke up the following morning like I had a bad cold. My nose was clogged and tickled constantly until I sneezed and sneezed. That lasted about nine hours, then disappeared the next morning.

Unfortunately some douche-bags broke all the ATMs and did this as well on people’s homes and businesses. Not cool:

Despite this event, I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. Istanbul is super-cool; the people are very friendly. It’s a strange mix of opposites, a mash-up, if you will: Asian-European; old-new; mosques, churches and synagogues; influenced by Mediterranean produce but also by the fruits and vegetables and grains of Iran, Iraq and Syria, which it borders. Tribal textiles, Venetian glass.

There is no anti-American sentiment by the people, according to our guide Alp. He said that, while it’s within people’s rights to protest, sometimes what they do can be more harmful (see graffiti above), and the shops on Istiklal closed early the night of the protest, losing revenue. Maybe also the tourism numbers will decrease as they did after June, he said.

But his message: “This is not about Americans.”

First photo by